by Rosie Martin

by Rosie Martin

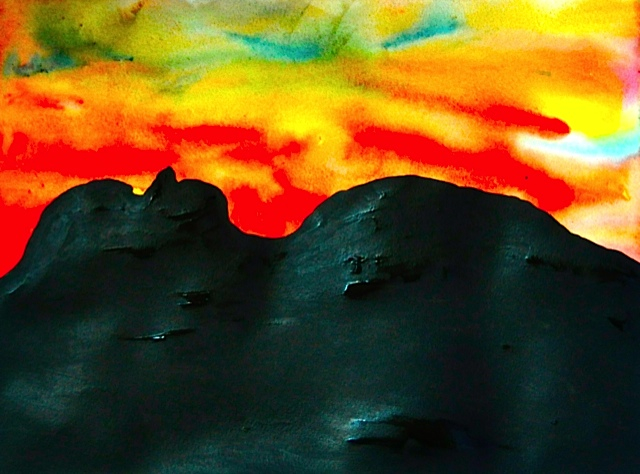

Without any effort or intention, without willing it to be so, an image of a glass of water appeared in my mind. It thrills me when visual metaphors shimmer into place, for I have learned that they explain me to me in some surprising way.

Into the clear water dropped a bloodied tear of cochineal – bomb-like, turbulent, and spreading thinly, evenly, rapidly – forever changing the whole. This is what happened to my mind. In prison.

I have been doing some work in the prison. You see, I know how to teach people to read. I realise this sounds ordinary, but there is a lot of science to know, about what’s going on in the brain and mind of someone who doesn’t learn to read in the usual way. It’s anything but ordinary. I pour and pour into this work.

Two years ago I was sitting in an auditorium in which a plea was being made for volunteers to work at literacy tasks with prisoners. My colleague, who likewise pours and pours, was also there. At the end of the event, as we walked toward each other looking into each other’s faces from across the room, we knew simply what the other was thinking – we know how to add quality for these complicated souls unable to respond to regular methods of learning to read, we have the skills, we ought to be gifting this knowledge to these vulnerable men and women. In the moment my eyes met hers, I felt in my depths, a breathless sparkle like bright flow between river stones – vivacious élan which I have come to recognise as my herald of heart action.

Now, it’s a practical world that we live in and impetuous dash and ephemeral sparks have less to offer once an idea has a shape, for then of course, there is work to be done. So I rang the prison, and asked if I could come, bringing with me the skills splashed and filtered in through time in my craft, to tell about what I can do. Well – my hat is off and my shoulders are bowed – I have nought but respectful admiration for the workers in that place who consistently enabled me and showed gratitude. ‘Come, show us, tell us’, their instant reply.

Now, I’m a newcomer. Not to the work, but to this environment and this cohort. The principles to teach reading to those who have been unable to learn it are sure. Analyse each individual’s configuration of processing skills, set a plan designed for that configuration and direct-teach a hierarchy of skills at the just-right level of challenge. And all the while, honour the soul of he thus configured with warmth, patience, humour and the dignity of no judgment. These principles work. Skills can be grown. And I saw myself unfazed by the hand scans, magnetic locks and clanging doors, for a mind is a mind and a heart is a heart, no matter where they are housed. Or warehoused.

This was the glass of water in the image of my prison experience – all this, clear and contained.

But I’m a newcomer to working at the prison and it’s not dream and sparkle and vivacity for they thus housed. For many – for most – the way of things has not been like the way of my things, but more like this: I can’t read, can’t access education, can’t get work – I’m poor. And another axis: what is tender communication(?) it has touched me so rarely(!), language is weak, vocabulary and knowledge diminished, can’t get work – I’m poor. And there are many other axes of disadvantage. Smashing, shattering axes of disadvantage shocking with tortured horror and foisted upon men and women when they were but sweet and soft-cheeked boys and girls. Through no fault of their own. Ergo, therefore – made poor.

I am reminded that miserable souls were transported to Pt Arthur bound in body and mind with the chains of events sprung of poverty. I’ve imagined those cold and wretched men. And all these years later, I stand in the gaze of souls transported to Risdon, also bound in body and mind with the chains of events sprung of poverty.

And here bombed the bloodied tear that suffused my mind in prison. Not enough had changed in two hundred years. Souls born into crippling vulnerability were then transported behind bars – and they are still being transported behind bars. These bars, the materialised versions of those already built into their minds and lives through too little of the salve of society’s tenderness upon their developing beings and impoverished stations. Bloodied poverty. Bloodied lack of compassion. The ruddy tear swept through me.

Yet I note that time settles and changes the discernment of murky waters. For I see that my community now imbues the wretched of Pt Arthur with esteem and affection – a response of compassion two hundred years too late for those lives. Their odour and base mouths are not so much now forgotten, as that without the revulsion of sensory impact, these unsavoury qualities are not even considered when convicts’ stories are told. Judgement of their crimes, likewise, is not now forgotten, but rather is barely considered; for absent now is the unclad emotion of the perpetrated and the foaming of the virtuous. Now, only the mistreatment and the humanity of those hapless are left for us to see. And they are found wretched, and heroes; revered for their human worthiness.

Time does indeed settle and change the discernment of murky waters. For I also note that the respectable of old London and Hobart towns have not withstood the judgement of time quite so well. Popular hindsight now finds heartless fault in these of the ceiled and comfortable houses, clean and cologned, sending wretches to the end of the earth for the loss of a fop’s handkerchief. Now, as we appraise, their humanity seems to have been absent and their stories are imbued with stony hardness; the London cold upon their hearts.

But it is me I see surveying the glinty image in my mind. Bloodied tear to rosy clarity. My standing and my Chanel are respectable in my era. My insured wide-screen, the fop’s handkerchief. My aversion to human pungence, the pharisaic disgust. My lack of compassion, the lock upon the chains.

Tenderness, compassion, warmth and forgiveness are in the full-blooded cochineal concoction to pour and pour upon poor – to recolour with beauty the crippling abhorrence of smell, filth and profanity; and eventually even to ease the slicing agony of the pared and naked emotion which rises in the anguish of offence. Poverty to the end of the earth I say, not the poverty-stricken. Lest we all be destined to poverty in the wholeness of our beings.

This rosied glass is not new. I’m just the newcomer who teaches people to read. Yet I’m clear that I know this: the tools of my craft – warmth, patience, humour and the dignity of no judgment – are amongst the simplest tools of the empowerment of humankind. They and their stable mates, some with much loftier names, have been written of for centuries. Many shimmering images in the minds of many have brought forth wise words pointing toward these strong and gentle tools, well-oiled. We know how they are used because we have felt them at work in our innermost beings. They are the underrated means with which large change must be crafted. If we can be courageous, and feel their weight, their fit within our hands; and use them, even when it takes grit of the heart to do so – for love is a verb. A doing word. And a mind is a mind and heart is always heart – no matter where housed.

Writers’ bio:

Rosie Martin is a Hobart-based speech pathologist specialising in intervention and support for people of all ages with literacy impairments and social communication impairments. She has recently founded a benevolent organisation, Chatter Matters Tasmania, to assist with bringing these supportive services to the most disadvantaged in our communities.