Patrick dropped me off at the station. ‘Let me know,’ he continued. ‘The sooner the better, because sorting things out with Duane could take some time.’

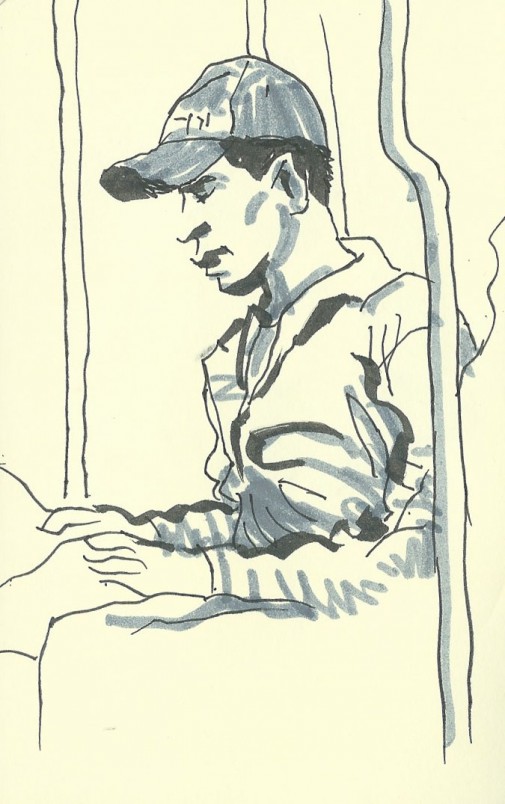

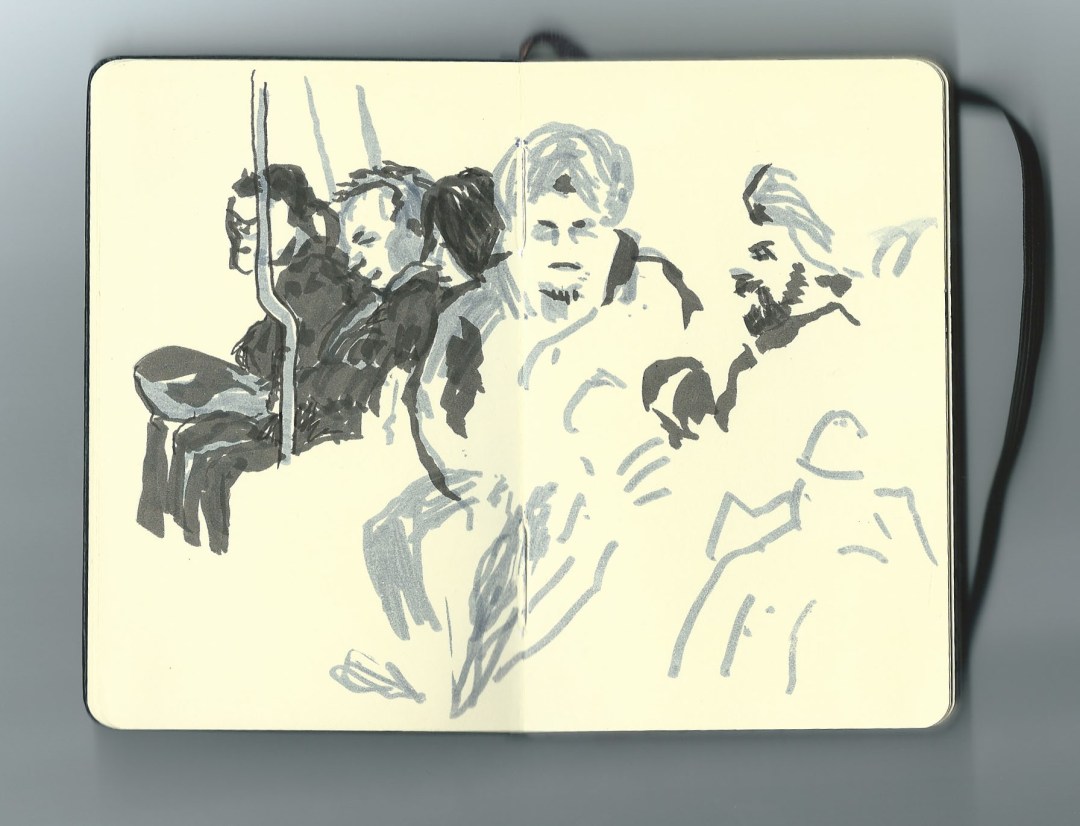

The journey home was quicker than I wanted. Soon I was navigating the blustery granite angles of Kings Cross. At the hostel, the weekend crowd was checking in. Uni students, mostly, down in London for a party weekend. They booked months in advance, pushing out the tide of people washed up from all corners of the EU and further afield. It was a Friday, so I had to move. My standards had lowered with my bank balance. Gone were the days of four bed all-female dorms, hairdryer and toiletries included. The new dorm was practically in the basement. A Tetris nightmare of cheap metal bunks, on entering I was greeted by the familiar odour of cleaning chemicals and bodies stewing on stale sheets. No windows. But it was quiet. The dorm was empty.

I turned on the lights and hung my towel over the railing at the end of the bed. Next to me, someone had done the same thing. An elaborate curtain was rigged up out of sheets. Taking advantage of the unexpected privacy, I began to undress. The position of the room gave me plenty of warning if someone was coming. I tugged off my jeans and threw my t-shirt into the corner of my suitcase reserved for dirty clothes. My bra was almost off when a haggard face briefly appeared from behind the sheet curtain next to me. I screamed, and he retreated. We never spoke, but on a few occasions that night his rough damp foot brushed against mine. The thin wooden bunk dividers were only waist-high. In the morning I rang Patrick. This time there was no hesitation. ‘I’ll take the room,’ I said.

I didn’t stay there long, a few months at most. Like I had suspected, the small print was a disclaimer, authorised by Patrick’s conscience. He continued to be slippery about prices and I had no allies once Daria was evicted. She threatened to take him to court over the illegal extensions, but that’s another, longer, story. I saw Duane once more, soon after moving in. There was a big black guy outside Tooting station in some kind of awkward dispute. He might have been asking for money. Maybe it wasn’t him, we only crossed paths briefly. Anyway, I’ve left Tooting behind. Recently I got a new job, front-of-house at a hotel in Mayfair, so I’m crossing the Thames, moving up, moving on. I found a little bedsit in Kilburn. It’s a start. Before leaving I went down to the station to try and find Duane. I wanted to tell him he could have his room back, but I couldn’t find him. I suppose he’s probably moved on as well.

Writer’s bio:

Georgia Mason-Cox is a Tasmanian-born writer living in Sydney. Her London adventures took her from dishwashing, to charity collecting, to working for the Royal Household. This is her first published work. It is fiction, just.