Sometimes Dreams Are Simpler Than You Think

by Fiona Lohrbaecher

I’ve always been fascinated by the hidden language of dreams, those subtle psychological promptings of the subconscious. I used to read books on decoding their mysticism and slept with a dream diary by my bed. I looked forward to sleeping, to wandering rapt through that wyrd and whimsical world where anything is possible. Upon waking I wrote the images down before they melted in my mind like candyfloss in the mouth; substance gone, leaving only a sweet taste and a vague remembrance. A lost world, a lost paradise.

I’ve always been fascinated by the hidden language of dreams, those subtle psychological promptings of the subconscious. I used to read books on decoding their mysticism and slept with a dream diary by my bed. I looked forward to sleeping, to wandering rapt through that wyrd and whimsical world where anything is possible. Upon waking I wrote the images down before they melted in my mind like candyfloss in the mouth; substance gone, leaving only a sweet taste and a vague remembrance. A lost world, a lost paradise.

Recurring dreams in particular intrigued me; what was the deep, important message my psyche was trying to communicate? For years I was troubled by one particular dream. I was in a large shopping mall, a maze-like complex, trying to find the basement food court where a delicious array of vegetarian Thai food awaited me. But, as is the nature of dreams, I never could find it. I wandered up and down staircases, along corridor upon corridor, never reaching my heart’s desire.

I agonised over the meaning of this dream, never interpreting it satisfactorily. I knew that a house represented the mind; the different floors the different levels of being and consciousness. I wondered why I was always wandering to the basement, rather than trying to work my way upwards. For years the true meaning of my dream eluded me, slipping through my fingers like a handful of melting ice-cream.

Three years ago we set off on a big tour of the mainland. We set sail from Tassie, hit the north island and headed west. It was ten years since we’d last been in Western Australia, our original landfall in the Great Southern Land.

Re-exploring Perth with the children, lunchtime came around. We were in the mall. I remembered that the Carillon Shopping Centre had a good food court. We entered the large multi-storeyed shopping centre. A maze of corridors and levels confronted us. We took the escalator down, wandered along several corridors, a wrong turn here, a right turn there, descended another staircase, negotiated several more confusing corridors and finally found the food court. And there was the vegetarian Thai food stall. I stopped dead. A bell rang in my head. It’s a cliché but emotion really did well up in my chest and threaten to choke me. A lump rose in my throat and my breathing was fast and shallow. This was it! This was the place of my dreams, the food court that I had spent 10 years longing for and dreaming of!

And I realised then and there that sometimes our dreams are a lot simpler than we think; sometimes the message really is as simple as it looks, not a cryptic array of hieroglyphics waiting to be translated, overanalysed. And that the message of my dream, the clear, undisputable message was: that I have a deep and strong spiritual connection – with food!

Women and Minorities: Part III

Patrick dropped me off at the station. ‘Let me know,’ he continued. ‘The sooner the better, because sorting things out with Duane could take some time.’

The journey home was quicker than I wanted. Soon I was navigating the blustery granite angles of Kings Cross. At the hostel, the weekend crowd was checking in. Uni students, mostly, down in London for a party weekend. They booked months in advance, pushing out the tide of people washed up from all corners of the EU and further afield. It was a Friday, so I had to move. My standards had lowered with my bank balance. Gone were the days of four bed all-female dorms, hairdryer and toiletries included. The new dorm was practically in the basement. A Tetris nightmare of cheap metal bunks, on entering I was greeted by the familiar odour of cleaning chemicals and bodies stewing on stale sheets. No windows. But it was quiet. The dorm was empty.

I turned on the lights and hung my towel over the railing at the end of the bed. Next to me, someone had done the same thing. An elaborate curtain was rigged up out of sheets. Taking advantage of the unexpected privacy, I began to undress. The position of the room gave me plenty of warning if someone was coming. I tugged off my jeans and threw my t-shirt into the corner of my suitcase reserved for dirty clothes. My bra was almost off when a haggard face briefly appeared from behind the sheet curtain next to me. I screamed, and he retreated. We never spoke, but on a few occasions that night his rough damp foot brushed against mine. The thin wooden bunk dividers were only waist-high. In the morning I rang Patrick. This time there was no hesitation. ‘I’ll take the room,’ I said.

I didn’t stay there long, a few months at most. Like I had suspected, the small print was a disclaimer, authorised by Patrick’s conscience. He continued to be slippery about prices and I had no allies once Daria was evicted. She threatened to take him to court over the illegal extensions, but that’s another, longer, story. I saw Duane once more, soon after moving in. There was a big black guy outside Tooting station in some kind of awkward dispute. He might have been asking for money. Maybe it wasn’t him, we only crossed paths briefly. Anyway, I’ve left Tooting behind. Recently I got a new job, front-of-house at a hotel in Mayfair, so I’m crossing the Thames, moving up, moving on. I found a little bedsit in Kilburn. It’s a start. Before leaving I went down to the station to try and find Duane. I wanted to tell him he could have his room back, but I couldn’t find him. I suppose he’s probably moved on as well.

Writer’s bio:

Georgia Mason-Cox is a Tasmanian-born writer living in Sydney. Her London adventures took her from dishwashing, to charity collecting, to working for the Royal Household. This is her first published work. It is fiction, just.

Women and Minorities: Part II

Patrick drove fast, gliding around corners and talking about his investments. The villain of the piece was a real estate agent, but this was separate to his job – this was his own property he was renting out. It was just around the corner, he said. The protracted drive built up expectations that crumbled unceremoniously as he began to slow down. ‘I like my tenants to have an education,’ he said, hastily parking.

The house was medieval brown and squatted at the end of a wistfully named street. Inside was a maze of stairs and corridors. Patrick was in a hurry. I lagged behind, struggling to reconcile the puzzling dimensions of the house’s interior with the modest proportions visible from outside. We passed three distended washing machines and a big yellowish sink. ‘The laundry,’ said Patrick. His shiny winklepickers lacked grip on the scrappy lino and he steadied himself on a small bar fridge. ‘Also the kitchen.’

We climbed the stairs. Chipped bannisters and peeling paint. Medium furnished room. The first floor smelt of fat and onions. All utilities included. Scraggy carpet and sweating walls. Women and minorities welcome. Abruptly Patrick turned left, stopping outside a door littered with faded Pokemon stickers. ‘This is the one,’ he said, unlocking it. A woman inside yelled out, and we both jumped.

‘Christ!’ Patrick crossed his arms and stood with his back to the door. ‘Are you decent?’ he said, and stuck his head inside. ‘Daria, I’m afraid you owe me more rent.’

‘No! This is not what we agreed!’

‘We agreed you would be out by now.’

They argued, and I studied the floor. After a minute, Patrick glanced my way. ‘Do you want to….’ He nodded towards the room.

‘No, it’s okay.’

‘Don’t worry about her, she shouldn’t even be here.’

The room was cramped but scrupulously tidy. I did a quick twirl, enough to get a general sense of the space, before backing out. Downstairs, he asked me what I thought.

‘That lady – Daria – she’s definitely moving out?’

‘She – she’s Polish or something, she’s been nothing but trouble.’

I confirmed the price. Patrick’s intricately gelled hair seemed to wilt a little. ‘What did I say? Is that what I said?’

We faced off over the boot of his car. ‘The ad said all utilities included.’

‘You must want the other one.’ He started to explain when his phone began to purr. ‘I’ll have to take this,’ he said, walking a little way up the street. I jammed my hands under my arms to keep warm. Patrick seemed agitated. I heard the word depression, several times. Then, ‘It’s news to me he’s unemployed.’

Patrick returned to the car, shaking his head. ‘I’ve just had his mother on the phone. She’s not happy because she says he has issues and he’s better off living with her and sorting them out.’

‘Who’s this?’

‘Duane. The one in your room. The room you said you wanted.’

I followed him back inside. Patrick had advertised two rooms and shown me the wrong one. ‘I leased it to Duane purely on a trial basis,’ he explained, climbing a newer, different staircase. ‘But nothing’s settled yet.’ We walked to the end of a dim hallway. There was nowhere to go from here.

‘Duane!’ Patrick banged on the door. ‘I’ve just had your mother on the phone!’

Barefoot in shorts, Duane was silent and motionless in the doorway. His fingers clenched and unclenched an open packet of jaffa cakes. Eventually he stepped back, allowing us a little way into the room. It wasn’t much wider than the flat screen TV wedged at the foot of the single bed.

‘I’ve just had your mother on the phone,’ Patrick repeated. Duane winced. After the second time I realised it was a nervous blink. He looked away. I thought Patrick had stared him down but Duane was in fact looking behind us. We tried to turn around too, bumping shoulders and stepping on each other’s toes, and I found myself face to face with the small figure on the bed that I’d tried so hard to avoid seeing just a few minutes earlier.

Daria stood in the hall. She looked determined, but maybe she was just cold. Her ugg boots looked like they’d stolen all the fluff from her dressing gown.

‘The pilot light, Patrick. It fucking goes out even when a little breeze is coming.’

Patrick grunted and disappeared down the hall. Now it was just me and Duane.

‘Mothers can be difficult,’ I said. He remained silent. Shoulders squared, he could have been wearing a combat uniform rather than a stained t-shirt that read ‘phat papa’. I wondered why his room was the only one without a bulky padlock on the old-fashioned swinging latch.

‘Mostly,’ I continued, ‘they just want the best for you.’ I couldn’t look at Duane, so I let my eyes drift up to the small high window. A few frigid trees against a restless sky. Duane still wasn’t talking.

‘What do your parents want you to be?’

‘Afro-Caribbean,’ he said, disbelieving. I nodded quickly but he called my bluff. ‘Doctor, lawyer…’

He sat on the bed. ‘Sorry about this,’ I said. We waited in silence. ‘It’s a good little room,’ said Patrick when he returned. ‘Duane, we’ll talk.’

‘He’s dropped out of college too,’ confided Patrick as we went downstairs. ‘Actually I think his mother has a point.’

In the car we got down to business. ‘I’d take it,’ I said, carefully locating my enthusiasm in the realm of the hypothetical.

‘As I said, I like my people to be educated.’

‘I’ll think about it.’

Writer’s bio:

Georgia Mason-Cox is a Tasmanian-born writer living in Sydney. Her London adventures took her from dishwashing, to charity collecting, to working for the Royal Household. This is her first published work. It is fiction, just.

Women and Minorities: Part I

The room was cheap, but ‘cheap for London’ wasn’t the same as being affordable. I scrutinized the ad. Of course it was a shared house (‘we are six friendly Eastern Europeans’) but I couldn’t expect to go straight from a crowded hostel to my own flat. I had to be realistic, but there were some things I wouldn’t compromise on. Balancing my laptop on my knee, and resting one arm protectively on my bag, I found the crucial information in the third paragraph: Royal Albert was the closest public transport link. After clicking through the photos, I concluded location was about all it had to recommend it. The rooms were dark and severe, with incongruous touches of chintz. But when the hostel looked like a school camp that had hosted a bucks’ night, what was a bit of jarring interior design? For central London it wasn’t a bad deal.

I was on the Beckton branch of the Docklands Light Railway when I realised Royal Albert had nothing whatsoever to do with the Royal Albert Hall. The address was in fact way out east, beyond the loop of the Thames. Still believing geographical isolation caused its metaphorical equivalent, I had no desire to tempt loneliness by being stranded out in no-man’s land. But there were worse things than a hostile flat. With its air of quiet paranoia, its rules and complex hierarchies, the hostel sometimes felt more like a low-security prison. If I didn’t get out soon I’d become a lifer, hanging around the common room and dishing out advice on the best time to get a hot shower and where to find a power point.

So I stayed on the DLR, and did some belated location research. Google said it was a good place to watch the take-off and landing of planes. The scenery had a low-rise bleakness common to the immediate vicinity of airports. Overpasses loomed briefly, a concrete blur. Things soon came into focus once I stepped out into the rain. Factories and fly-tips dominated the streetscape. Eventually I found the house. The front yard announced itself by extending an uneven carpet of cracked pavers onto the road. A few rubbish bins, huddled together for warmth, were the only obstacles to the front door. Now it was only curiosity impelling me to knock.

Bogdan was a Bulgarian security guard with a boxer’s nose. He owned the place; we had talked on the phone. Charming and proprietorial, he led me inside. ‘It is very good possibilities for the renovation,’ he announced. We toured the ground floor. The décor was eclectic, like a hermit and an Orthodox priest had fallen out over furnishings. I asked who else lived there but Bogdan didn’t hear me. Distracted, he used his foot to nudge a thigh-high leopard-print welly out of our path. ‘Anastasia’s,’ he muttered. ‘We go up!’

I sat on the bed, observing Bogdan observing me pretending to observe the space. It was quiet, a long way to the high street. In fact it felt a long way from anywhere. Bogdan said there was a short-cut to the Tesco’s. He told me about the other tenants, pointing out their rooms: a Latvian student in that one, a Polish couple next to her, a young Estonian woman over there. As he showed me the upstairs bathroom I peeked into the half-open door beside it. Centre stage was a dressing table, weighed down by a shining sea of perfume bottles and jars of lotion that were reflected back in a vast wall-mounted mirror.

‘Who lives there?’ I asked, imagining an exotic Russian showgirl – Anastasia, no doubt, the owner of the glamorous welly. Bogdan closed the door. ‘This is my room,’ he said.

Downstairs we chatted. He was about to go into business. There was a gap in the market for Slavic home gym equipment, and he knew some suppliers. Perhaps I’d like to be his secretary? But I’m only telling you this for context – it has nothing to do with the actual story.

That begins a week later, with Patrick. I saw his ad at breakfast and had arranged a viewing by lunch. The small print troubled me but four words weren’t enough to put me off going. We met outside his office. Tooting was almost as far south as Royal Albert was east, but there was no mistaking it with any famous landmarks. ‘It’s a good area,’ said Patrick. ‘Lively.’ The wind gnawed at my knuckles and I pulled my sleeves down to cover them. He inspected me carefully. ‘I assume you’ve a job?’ I made my hands visible again, and told him I waitressed part-time. ‘Right,’ he said, unlocking a peach sports car. ‘Hop in.’

Writer’s bio:

Georgia Mason-Cox is a Tasmanian-born writer living in Sydney. Her London adventures took her from dishwashing, to charity collecting, to working for the Royal Household. This is her first published work. It is fiction, just.

Cochineal

Without any effort or intention, without willing it to be so, an image of a glass of water appeared in my mind. It thrills me when visual metaphors shimmer into place, for I have learned that they explain me to me in some surprising way.

Into the clear water dropped a bloodied tear of cochineal – bomb-like, turbulent, and spreading thinly, evenly, rapidly – forever changing the whole. This is what happened to my mind. In prison.

I have been doing some work in the prison. You see, I know how to teach people to read. I realise this sounds ordinary, but there is a lot of science to know, about what’s going on in the brain and mind of someone who doesn’t learn to read in the usual way. It’s anything but ordinary. I pour and pour into this work.

Two years ago I was sitting in an auditorium in which a plea was being made for volunteers to work at literacy tasks with prisoners. My colleague, who likewise pours and pours, was also there. At the end of the event, as we walked toward each other looking into each other’s faces from across the room, we knew simply what the other was thinking – we know how to add quality for these complicated souls unable to respond to regular methods of learning to read, we have the skills, we ought to be gifting this knowledge to these vulnerable men and women. In the moment my eyes met hers, I felt in my depths, a breathless sparkle like bright flow between river stones – vivacious élan which I have come to recognise as my herald of heart action.

Now, it’s a practical world that we live in and impetuous dash and ephemeral sparks have less to offer once an idea has a shape, for then of course, there is work to be done. So I rang the prison, and asked if I could come, bringing with me the skills splashed and filtered in through time in my craft, to tell about what I can do. Well – my hat is off and my shoulders are bowed – I have nought but respectful admiration for the workers in that place who consistently enabled me and showed gratitude. ‘Come, show us, tell us’, their instant reply.

Now, I’m a newcomer. Not to the work, but to this environment and this cohort. The principles to teach reading to those who have been unable to learn it are sure. Analyse each individual’s configuration of processing skills, set a plan designed for that configuration and direct-teach a hierarchy of skills at the just-right level of challenge. And all the while, honour the soul of he thus configured with warmth, patience, humour and the dignity of no judgment. These principles work. Skills can be grown. And I saw myself unfazed by the hand scans, magnetic locks and clanging doors, for a mind is a mind and a heart is a heart, no matter where they are housed. Or warehoused.

This was the glass of water in the image of my prison experience – all this, clear and contained.

But I’m a newcomer to working at the prison and it’s not dream and sparkle and vivacity for they thus housed. For many – for most – the way of things has not been like the way of my things, but more like this: I can’t read, can’t access education, can’t get work – I’m poor. And another axis: what is tender communication(?) it has touched me so rarely(!), language is weak, vocabulary and knowledge diminished, can’t get work – I’m poor. And there are many other axes of disadvantage. Smashing, shattering axes of disadvantage shocking with tortured horror and foisted upon men and women when they were but sweet and soft-cheeked boys and girls. Through no fault of their own. Ergo, therefore – made poor.

I am reminded that miserable souls were transported to Pt Arthur bound in body and mind with the chains of events sprung of poverty. I’ve imagined those cold and wretched men. And all these years later, I stand in the gaze of souls transported to Risdon, also bound in body and mind with the chains of events sprung of poverty.

And here bombed the bloodied tear that suffused my mind in prison. Not enough had changed in two hundred years. Souls born into crippling vulnerability were then transported behind bars – and they are still being transported behind bars. These bars, the materialised versions of those already built into their minds and lives through too little of the salve of society’s tenderness upon their developing beings and impoverished stations. Bloodied poverty. Bloodied lack of compassion. The ruddy tear swept through me.

Yet I note that time settles and changes the discernment of murky waters. For I see that my community now imbues the wretched of Pt Arthur with esteem and affection – a response of compassion two hundred years too late for those lives. Their odour and base mouths are not so much now forgotten, as that without the revulsion of sensory impact, these unsavoury qualities are not even considered when convicts’ stories are told. Judgement of their crimes, likewise, is not now forgotten, but rather is barely considered; for absent now is the unclad emotion of the perpetrated and the foaming of the virtuous. Now, only the mistreatment and the humanity of those hapless are left for us to see. And they are found wretched, and heroes; revered for their human worthiness.

Time does indeed settle and change the discernment of murky waters. For I also note that the respectable of old London and Hobart towns have not withstood the judgement of time quite so well. Popular hindsight now finds heartless fault in these of the ceiled and comfortable houses, clean and cologned, sending wretches to the end of the earth for the loss of a fop’s handkerchief. Now, as we appraise, their humanity seems to have been absent and their stories are imbued with stony hardness; the London cold upon their hearts.

But it is me I see surveying the glinty image in my mind. Bloodied tear to rosy clarity. My standing and my Chanel are respectable in my era. My insured wide-screen, the fop’s handkerchief. My aversion to human pungence, the pharisaic disgust. My lack of compassion, the lock upon the chains.

Tenderness, compassion, warmth and forgiveness are in the full-blooded cochineal concoction to pour and pour upon poor – to recolour with beauty the crippling abhorrence of smell, filth and profanity; and eventually even to ease the slicing agony of the pared and naked emotion which rises in the anguish of offence. Poverty to the end of the earth I say, not the poverty-stricken. Lest we all be destined to poverty in the wholeness of our beings.

This rosied glass is not new. I’m just the newcomer who teaches people to read. Yet I’m clear that I know this: the tools of my craft – warmth, patience, humour and the dignity of no judgment – are amongst the simplest tools of the empowerment of humankind. They and their stable mates, some with much loftier names, have been written of for centuries. Many shimmering images in the minds of many have brought forth wise words pointing toward these strong and gentle tools, well-oiled. We know how they are used because we have felt them at work in our innermost beings. They are the underrated means with which large change must be crafted. If we can be courageous, and feel their weight, their fit within our hands; and use them, even when it takes grit of the heart to do so – for love is a verb. A doing word. And a mind is a mind and heart is always heart – no matter where housed.

Writers’ bio:

London

London is the Great Beast; and through the injection of an aeroplane one is swept up into her blood stream, losing the identity of the individual to be a single blood cell, one part of an enormous creature. And one is pumped through tunnels underground – the veins underneath the skin; coursed through lines like biological systems and, churning in the swell of the other cells, bubbling up further to erupt! Gushing out through tube station doors and swept onto steps worn down by millions of steps over hundreds of years.

And you are born onto the streets looking up – into the light that peaks through the gaps, of peaks that dwarf you in their shadows as they reach up to the length of their stretch. And below, on the ground where we are, there is chaos from all sides as the hordes of suits and tourists blunder passed curbside salesman spruiking incomprehensible town-crier pitches. And there are a thousand signs – you can’t read them all, all bright and loud and demanding that you need whatever it is that is on them.

And you wonder if you lived here would you become one of them – would this define you? This city? For being a traveller I see people totally absorbed by this place; and I am superfluous to their requirements; London appears often indifferent to one’s presence and from all sides confidently reminds one that you need London; and London will most certainly survive without you.

And there’s a thousand accents and languages and dialects and incomprehensible colloquialisms and funny people and sad people and animated people and shy and rich and lavishly boisterous and poor and begging and lost and homeless and celebrity, lawyer, policeman and prince. They could be sitting next to me, some sort of royalty, but I don’t read the newspapers, nor do I watch television; and I treat everyone equally; and my occasional online glances are for conversation only.

And through the deep surges of passion and apathy echoes a warm glowing sensation occurring within – this feeling of being apart of something large, grand even, the feeling that one might heave on an axis and turn millions of people into a different direction entirely; being at once almost inconceivably small and magnificently important.

London. Her body divine – of bricks, cement, metal and glass. Shot up from the ground – buildings like flowers. London. Your old skin speaks without words – of the years and bodies and stories. London. Whose epitaphs – obelisk-esque – stand tall, elegantly iconic, endlessly inspiring, yet still – looking up, then looking down, one can not unnotice the wondrous gap between the dirty old stone floor; and the glorious and golden shiny peaks.

And the mirage is three hundred and sixty degrees wide; and it forces you around chasing your tail, coming back to similar places – the old haunts.

London. All your roads are full. All your doors are open. You’re Sinatra’s New York. You’re a place to make it. To be somebody. You’re a one hundred year old lemonade and there’s only one left. You’re a restaurant that specialises in mashed potato. And there’s the thought that the longer you walk the more roads become large rivers of cars and doors, one-by-one, close forever. Almost like you might wander round London, only to one day look in the shiny reflection of a shop front window and notice that you’ve become old; and wonder how it happened.

And you make a loyal friend at the Society Club, surrounded by the portraits – all leather-bound paper and ink, of Burroughs, Joyce, Wilde, Woolf and Bacon. And you write yourself in here, over a latte; and the background chatter, minimal dance, the coffee machine and staff. And we’re all here – at the Society Club; and everyone is reading, or writing, or planning. And the girl making the coffees gives you a look.

And you know as you sip your coffee, these moments will pass into eternity and will mean nothing at all very soon. And in the Society Club it could the 50s, or the 60s, or the 70s, but not the 80s, 90s, or now. We exist in a past tense – here, now; and we drown sweetly in Vintage, and Retro, and Nostalgia.

And as the dogs fight in a dance in the middle of the room, you think that the floor tiles should look like a chessboard. And you sit in a brick building that was constructed a hundred years before you were born; and you wonder at the history and stories the walls could share. And my coffee and the words come closer to the end. But the coffee will flow forever, and the words will never stop.

London. You beautiful maze that has a thousand million masks, that is a mirage upon each corner, who holds ghosts in your leather-tough hands. London, whose magic I found, whose feet brushed history, whose mind mingled with royalty. London. My city, my capital, my friend.

Writers’ bio:

Adonis Storr is an English-Australian Poet, Author, Event Organiser, Master of Ceremonies and former Radio show host. He created Tasmania’s ‘Silver Words’ which has hosted an incredible array of literary talent and has been published by the Society Club in London. He toured regularly in Australia including venues like the Cygnet Folk Festival, The Festival of Golden Words and Passionate Tongues Poetry.

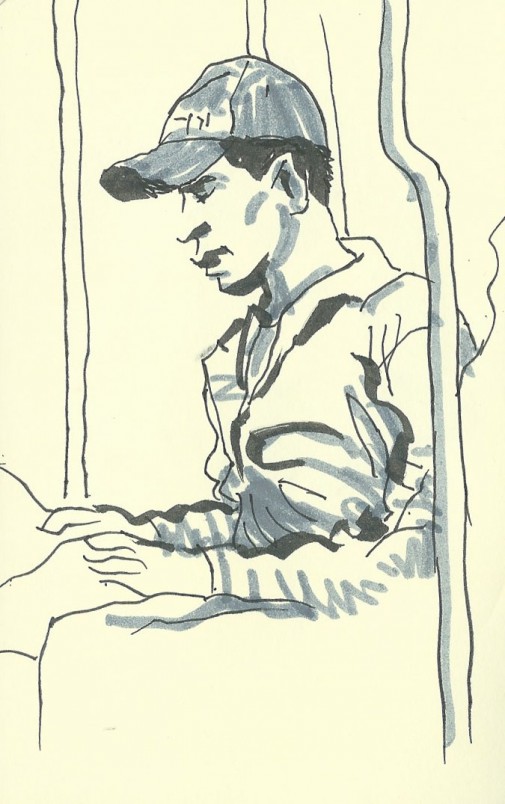

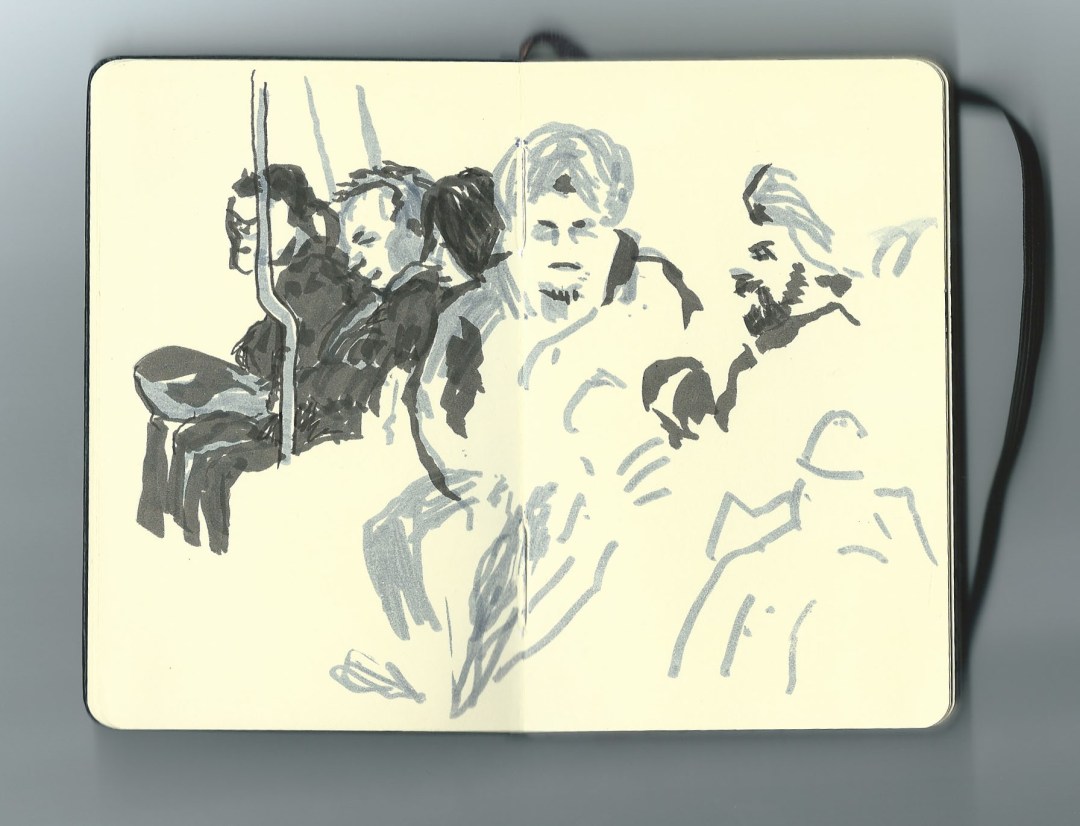

lines from the underground: writers respond to Tony Thorne’s illustrations

by Darren Lee

He was a Sentinel.

The Sentinels didn’t have names, at least not in the human sense. If he could have picked something for himself he would have settled on “Metro”; a name he kept seeing on the masthead of the free newspapers that the humans liked so much. The word stood out on the front page, bold and constant; he aspired to these attributes.

It was with the newspaper that Metro found a kindred spirit; like the strange, papery object he too spent most of his days loitering on the tube. This was his beat. He sat for most of the day, absorbing the rhythm and rattle of the carriage, observing closely the behaviour patterns of his fellow travellers: aloof, restrained and noncommittal. The humans hid behind their sheets of newspaper, hungrily devouring it with their darting eyes, before throwing them over their shoulders to litter their vacated seats. A fickle bunch, thinks Metro. Ripe for a takeover.

He coughs and a small specked feather escapes from his mouth. He had been briefed about this: nothing

to worry about, Control told him. The disguise had yet to be perfected. The rest of the Bakerloo passengers conform to type and don’t register anything untoward.

Metro is learning the Humans’ reading habit, but he mostly looks at the pictures: glittering people waving as they walk into a cinema, a plastic-faced man holding a battered briefcase aloft, a bloodied child crying amid rubble. As a Sentinel it’s Metro’s job to learn what he can and these abandoned items are good tidbits for his report; all nourishing breadcrumbs for a curious intellect.

On the way to Charing Cross he puzzles over a picture of a human female; he has seen her image before and is aware that she has elevated status within human society. She is showing her posterior to the camera. Metro doesn’t understand this and ponders if the backsides of the rich do not fulfil their original purpose; are they purely ornamental? He makes a note. This is something to brood over later with Control.

There is no danger of Metro going native. Control had warned him about that too: previous expeditions had turned and lost their avian nature. Metro thinks he saw one once in Regent’s Park. She was in the form of an old woman who sobbed openly as she tore up hunks of stale bread which lay uneaten at her feet. Her former brethren watched indifferently from the trees, forbidden to descend and peck at the tainted crumbs.

Metro is quiet and unmoving for most of the journey. It’s best for him to sit still; the disguise chafes his breast and his folded wings regularly cramp. There is some release when he reaches Charing Cross and he settles into the task of piloting his human shell to Trafalgar Square. His steps are tentative at first, but he eventually settles into a pattern, a stroll which syncopates with the bustle around him. Of all human activity, it’s walking that puzzles Metro the most. How did they cope with being

so earthbound all the time? Maybe this was why they distracted themselves so much with the rear ends of the great and good?

Metro bounds up the stairs to Trafalgar Square two at a time. He is showing off, trying to make a grand entrance. The crowds, too absorbed in taking photographs of themselves, fail to notice him. The birds sense his presence straight away; they immediately land and a silence spreads. They all look towards the corner where Metro is waiting.

A fat pigeon descends from Nelson’s hat and circles it’s way down the column, swooping over the silent brood. The pigeon gracefully lands at Metro’s feet.

Metro bends down and offers Control his hand. The pigeon rests upon his palm and is slowly elevated level to Metro’s face. The Sentinel launches into his latest report. After being confined to his disguise it feels good to revert to the old language once again.

Control listens patiently, processing all he can, hoping that among Metro’s theories on celebrity and transportation may lie the seed that grows into the humans’ final destruction. His flying army is ready, stationed on rooftops everywhere throughout the capital, ready to swarm as soon as the chink in the armour is revealed. Until then, the Sentinels arrive and share their knowledge.

Metro finishes his report and goes back to the tube.

Control flies upwards to his perch and defecates on Admiral Nelson. He continues his watch, making sure the world ends not with a bang, or whimper, but a bloody coo.

Tony Thorne’s illustrations, sketched while in London, travelling the iconic underground rail system will feature throughout the upcoming publication Islands and Cities, a collection of short stories by Tasmanian and London based writers. To celebrate this cross-cultural exchange, writers from the publication have each been assigned an illustration by Tony Thorne to respond to, for publication on our website.

lines from the underground: writers respond to Tony Thorne’s illustrations

About the size of a packet of cigarettes, the cheap plastic of the Buddha machine fits snug in my palm. It is simple- a speaker, a volume wheel, a switch, a red LED, a headphone port. A few basic circuit boards sit encased in what was once pristine white. I turn the wheel of the Buddha machine to its full volume and a loop begins to play in my ears. I close my eyes. Thirty seconds of gentle tones expanding and contracting, and then it repeats. I could turn the switch and another loop would come, but I am lucky. My breathing synchronises effortlessly with the ebb and flow of this first loop. I open my eyes.

It’s close enough to winter that the trees past the train windows are gilded with ragged leaves. People are wearing jackets, but not yet scarves or gloves. Everyone is too hot in this carriage. Past the noise of the Buddha machine, I can feel the train vibrate, I can almost hear voices. The loop is ambiguous- every noise that sidles past the headphones is incorporated until the train is breathing with me. Across the aisle men gesticulate and smile and talk. A girl is reading a book. A grey haired man looks pained as he casts his eyes around, oppressed by the weight of life pressed into the carriage. Beyond him in the gloaming I can see lights burning in office buildings.

It’s close enough to winter that the trees past the train windows are gilded with ragged leaves. People are wearing jackets, but not yet scarves or gloves. Everyone is too hot in this carriage. Past the noise of the Buddha machine, I can feel the train vibrate, I can almost hear voices. The loop is ambiguous- every noise that sidles past the headphones is incorporated until the train is breathing with me. Across the aisle men gesticulate and smile and talk. A girl is reading a book. A grey haired man looks pained as he casts his eyes around, oppressed by the weight of life pressed into the carriage. Beyond him in the gloaming I can see lights burning in office buildings.

We stop. We accelerate. We continue. We decelerate. We stop. We accelerate. We continue.

It feels as if there is a larger pattern, as if the loop is changing, as if it draws out – there is not. The change is in the train and in the passengers. This loop is thirty seconds long. The man next to me is reading a free newspaper. I am tired.

It feels as if there is a larger pattern, as if the loop is changing, as if it draws out – there is not. The change is in the train and in the passengers. This loop is thirty seconds long. The man next to me is reading a free newspaper. I am tired.

We reach my station and I step out onto the platform and the train keeps going, and the loop repeats.

Tony Thorne’s illustrations, sketched while in London, travelling the iconic underground rail system will feature throughout the upcoming publication Islands and Cities, a collection of short stories by Tasmanian and London based writers. To celebrate this cross-cultural exchange, writers from the publication have each been assigned an illustration by Tony Thorne to respond to, for publication on our website.

Slight delays on all services

“Sfuloo?”

“Nah, Rose, listen- it’s Cthulhu. CUH-THOO-LOO, yeah?”

Rose frowned and kicked at a pebble with her battered hi-tops.

“And you reckon it’s him in the underground?”

They were down a side street south of Waterloo station, far from picturesque skylines. The surrounding warehouses loomed in the tarnished glare of sodium streetlamps.

“Not IN,” Keith said, smiling, “UNDER. A three hundred metre tall octopus-elephant-beast-god-monster. You saw the badges, yeah? Something’s down there, and I reckon these guys are keeping him asleep. ‘Cos if he comes up it’s like end of the world-Armageddon Ragnarok APOCALYPSE level stuff, right?”

Rose smiled. She had seen the badges. They had spent days riding the underground checking members of staff. Each wore a little pin on their chest, a single point the size of a button with eight lines curving out from it. Most were silver, some gold. Keith swore he saw a jet black one on a guy at Marble Arch, but Rose hadn’t seen that. Sat in Keith’s flat, it all seemed fun, like signalling saucers from Primrose Hill, or trying to sneak cameras on tours of masonic halls.

Keith stopped in front of an anonymous steel door and consulted a battered A to Z.

“This is it,” he said. Rose leaned over his shoulder and looked at the map.

“Jubilee, Circle, District, Victoria, Northern,” Rose incanted. They had spent hours poring over maps of ley lines drawn by pagans. When you overlaid the ancient lines of power and the underground map, well… Rose was the one who noticed the nexus; one point circumscribed by the Jubilee, Circle, District, Victoria, and Northern lines- the point just south of Waterloo.

“The deepest point of the London underground,” Keith had said, and they had grinned.

“What do you think is down there?” Rose asked. Keith’s eyes sparked.

“I’ve got my ideas. I need to check some sources. I’ll tell you when we go down…”

This was what they did for fun- Rose didn’t drink, not after seeing her dad drink. Keith wasn’t good with people. So they followed clues, they tramped across the city. It filled time, it was fun, and it hurt no-one. They had spent a month tracking the grave of the Hampstead vampire and had ended up lighting some candles and leaving garlic and crosses over their top suspect’s tombstone. They had spent weeks conspiring to steal the London Stone, before Keith decided it was too dangerous— if the Stone left London, the city would fall. This was the way it had been, for years now. Rose wanted was to be part of something bigger- Keith helped her.

The tube strike was a blessing. No trains to worry about, no people, no electrified lines. The door was unlocked, swinging open onto darkness at Keith’s touch. He grinned at Rose and held a finger to his lips and they began the descent.

Seventy feet down and two hundred feet south they heard the footsteps. Keith grabbed Rose and pulled her tight to the wall and they turned off their head torches.

Silence.

Footsteps.

“Transport police— stop right there!”

Suddenly there were torch beams crisscrossing their paths, blinding their eyes. Rose tripped on a railway sleeper and fell, her face and hands landing in rough gravel inches from a rail. Would that rail be electric? She didn’t know. She was breathing so hard she thought she might burst. She could hear Keith scuffling behind her. She stared at the rail until she was roughly picked up.

“What’re you up to?” asked one, whilst another leafed through Keith’s A to Z. He stopped on a page and showed it to a few of the others. They stared at Keith and Rose then, and their faces hardened.

The officers walked them further down the tunnel and refused to be drawn out by pleading or questions or apologies. Finally they came to an opening, an arched vault where a dozen lines crossed.

Keith saw it first, and began to scream, swearing, shouting, struggling. Between the tracks there was hole— darkness thicker than ink, an onyx maw. An absence of light— a presence of darkness. Not brick or stone or mud— something organic. Rose’s eyes widened and she looked around for salvation. She saw the pin on the lapel of the British transport police officer holding Keith— a solid black point with eight curved lines spreading from its centre. Rose stared at it and then locked eyes with the officer.

“What’s down there? Sfuloo?” she heard her voice ask. Keith had stopped screaming, had started crying. The officers forced them to the precipice. Rose couldn’t stop herself from looking- blackness and darkness and endless depth and something else far below.

Movement.

The man holding her gave her shoulder a squeeze.

“Sorry love,” he said. He pushed, and Rose tumbled into the black, toward something bigger.

You can read, Water Birds, by Ian Green in the upcoming publication from Transportation Press, Islands and Cities, for updates on the release subscribe to our newsletter.

Writers’ Bio:

Ian Green is a writer from Northern Scotland. His short fiction has been performed at Liars’ League London, LitCrawl London, the Literary Kitchen Festival, and published in OpenPen London magazine. His work can also be heard on The Wireless Reader literary podcast and will feature in the upcoming short story anthologies Broken Worlds by Almond Press. His story Audiophile was a winner of the BBC Opening Lines competition 2014 and was produced and broadcast by Radio 4.