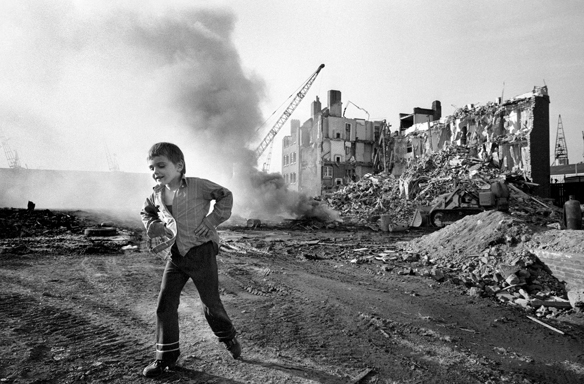

London editor, Sean Preston looks at the island that isn’t an island, at odds with itself and the relentless change of the city it sits within.

London editor, Sean Preston looks at the island that isn’t an island, at odds with itself and the relentless change of the city it sits within.

You can go to The Isle of Dogs now, and you’ll still find ‘indigenous’ Islanders there. They’re fewer and farther between, but they’re there. But it doesn’t overturn the change of pace and face to the Island. House prices are of course indicative of its popularity. I see the same in Limehouse. The Occupyists and ‘Shire artistes squat in derelict shops and the onset is forged: The rivers will run red with their watercolours. In time, my road will fall much in the way of the rest of East London. Those that have moved here, often seeking to oppose the banking establishment, are those that trendify an area. And they have a right to, I believe. There’s no point in begrudging London’s nature, for London has always been tidal. Is this tide synthetic? Probably. I’ll not be quashed by many for suggesting that, generally, in this city, like all others, wealth will have its way.

President Ted Johns of the Republic of the Isle of Dogs didn’t stand for it for long and I believe his method of ridicule and farce as a political tool made much sense. I have argued, perhaps to my detriment in some corners, that trolling is the great art of our time. I really do believe that to be the case (and look at it this way, if it proves not to be, I can always pretend I was just trolling). From his presidential home, which was in fact a small council flat on the Island, Johns and family presided over the new republic and, significantly, invited the world’s media into their home, their lives, their nation. The passports, barricades, immigration documentation, to me, are important artifacts of post-war London. And the newspaper cuttings even more so. It is known to us by now that to live by the media is to die by the media, and so it was with the independent state. The fortnight of coverage brought with it exposure of the squalor that even The Times called “Victorian”, but caused enough of a stir upstairs that the full tabloided onslaught was visited upon it.

Humour, bizarrely, has to be at the centre of our endeavours against those that seek to garrote social equality. Irony as a defense mechanism is nothing new; it’s unreservedly London, English. Literature has a part to play in this, and has been the primary canvas of insurrection and mockery for as long as we’ve scribbled. It’s hard to know how relevant, or how conspicuous this form of literary fiction can be in the century already well underway. I suppose the one thing about the oppression of opinion labelled extreme by those that gain from doing so, is that it requires the artist – the writer – to augment their creativity, just as Ted Johns did, abruptly, sensationally, for a fortnight in 1970.