Hey London – what did you get up to on the weekend?

This weekend in Hobart, I went to an art exhibition and saw a video piece by Georgia Lucy who had hung a hundred corn chips from a backyard clothesline – a hills hoist. Each bright orange triangle was strung up with a plastic clothes peg and fishing line. They fluttered like a mobile. Georgia cranked the clothesline handle to move the hoist up and down and the chips floated and jerked towards bowls of salsa and guacamole set up on red bricks near a sprinkler that came on intermittently to water the grass.

On Saturday night, I went to a party at a giant share house with a smoke machine set up in a downstairs room full of blurry people dancing. At the party I met one of the housemates who is from England and back in Hobart for a second time. I asked him why he had come back, and he said there is something about Tassie. I don’t disagree and wonder if by the place he meant people too, and if the two factors don’t become pretty close to the same thing in choosing a place to live.

I’ve never lived in London but I’ve been there. Not with much money though. Your pound swallowed my dollars and I mostly ate fish n chips so I still had money for (warm?) beer.

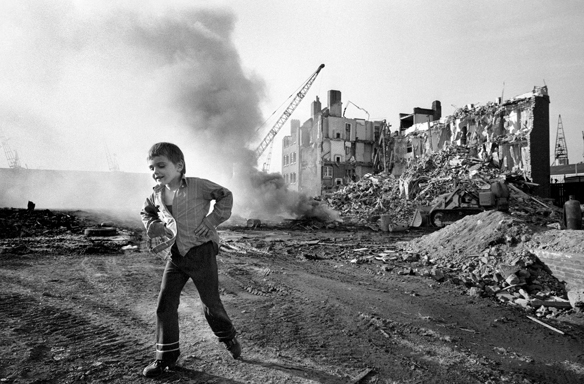

When I was in London the Olympics were on and your TVs didn’t mention anything about the Australians winning medals, which I found more unsettling than I thought I would. I picked blackberries from the laneway behind a house in Chingford that looked like all the other row houses. I caught the Tube into the centre from Walthamstow station and the double decker night bus back to Charing Cross. At the Notting Hill Carnival I was crushed against a barrier as a truck with a hip hop band on the back passed over a bridge creating a bottleneck and had to literally unplug to calm everyone down. It scared me because of how many people there were and how frenzied everyone became when we started to panic. Every time I watched the news it seemed like another teenager had died in a gang related shooting.

I didn’t work in a bar or drink Fosters or live in a shoebox-sized flat with fifteen other Australians. But I probably would have enjoyed doing that if I had for a while at least. I flew home. The trip was over like the weekend.

Today I drove to work because I got out of bed late and ten minutes went by with the radio on so I could listen to the news, trying to reconcile what I feel like I should know versus what I can remember. I found myself hopelessly tuned into the national traffic report – a car and truck collided on the approach to Woolloomooloo outside of Sydney – road closures in Blacktown due to scheduled maintenance on Bundgarribee Road, West, between Balmoral Street and Craiglea Street.

In contrast Hobart has been fine, said the presenter, before he looked towards Adelaide, also nothing much to report, and out across the Nullarbor to Western Australia.

Against a collection of stories, I arrived. But as I start to plan my week I’ve been thinking, like all good escape artists do – what is it like to live in London? What is it about that place? And what do you get up to on the weekend?

You can read, Manhattan is an Island, by Claire Jansen in the upcoming publication from Transportation Press, Islands and Cities, for updates on the release subscribe to our newsletter.