Sometimes Dreams Are Simpler Than You Think

by Fiona Lohrbaecher

I’ve always been fascinated by the hidden language of dreams, those subtle psychological promptings of the subconscious. I used to read books on decoding their mysticism and slept with a dream diary by my bed. I looked forward to sleeping, to wandering rapt through that wyrd and whimsical world where anything is possible. Upon waking I wrote the images down before they melted in my mind like candyfloss in the mouth; substance gone, leaving only a sweet taste and a vague remembrance. A lost world, a lost paradise.

I’ve always been fascinated by the hidden language of dreams, those subtle psychological promptings of the subconscious. I used to read books on decoding their mysticism and slept with a dream diary by my bed. I looked forward to sleeping, to wandering rapt through that wyrd and whimsical world where anything is possible. Upon waking I wrote the images down before they melted in my mind like candyfloss in the mouth; substance gone, leaving only a sweet taste and a vague remembrance. A lost world, a lost paradise.

Recurring dreams in particular intrigued me; what was the deep, important message my psyche was trying to communicate? For years I was troubled by one particular dream. I was in a large shopping mall, a maze-like complex, trying to find the basement food court where a delicious array of vegetarian Thai food awaited me. But, as is the nature of dreams, I never could find it. I wandered up and down staircases, along corridor upon corridor, never reaching my heart’s desire.

I agonised over the meaning of this dream, never interpreting it satisfactorily. I knew that a house represented the mind; the different floors the different levels of being and consciousness. I wondered why I was always wandering to the basement, rather than trying to work my way upwards. For years the true meaning of my dream eluded me, slipping through my fingers like a handful of melting ice-cream.

Three years ago we set off on a big tour of the mainland. We set sail from Tassie, hit the north island and headed west. It was ten years since we’d last been in Western Australia, our original landfall in the Great Southern Land.

Re-exploring Perth with the children, lunchtime came around. We were in the mall. I remembered that the Carillon Shopping Centre had a good food court. We entered the large multi-storeyed shopping centre. A maze of corridors and levels confronted us. We took the escalator down, wandered along several corridors, a wrong turn here, a right turn there, descended another staircase, negotiated several more confusing corridors and finally found the food court. And there was the vegetarian Thai food stall. I stopped dead. A bell rang in my head. It’s a cliché but emotion really did well up in my chest and threaten to choke me. A lump rose in my throat and my breathing was fast and shallow. This was it! This was the place of my dreams, the food court that I had spent 10 years longing for and dreaming of!

And I realised then and there that sometimes our dreams are a lot simpler than we think; sometimes the message really is as simple as it looks, not a cryptic array of hieroglyphics waiting to be translated, overanalysed. And that the message of my dream, the clear, undisputable message was: that I have a deep and strong spiritual connection – with food!

Richard Flanagan and the Global Literary Map

Ben Walter reflects on Richard Flanagan’s Man Booker prize win and whether this accolade will have a ripple affect on Tasmanian literary shores.

Here is what I knew about Tasmanian literature in the mid-90s. I knew that there was a literary magazine, Island, which my mother and step-father occasionally bought; these sat around the shelves – old, large-format Cassandra Pybus issues with writers’ faces and their leather jackets posing from the covers.

I remember reading what remains my favourite Tasmanian short story, The Sarsparilla Heights Writers’ Group Biennial Short Story Competition: Reading the Honourable Mention, by Pete Hay, and also a poem by Tara Kurrajong, who I later met very briefly through outdoor education circles at Rosny College. While walking up the side of Lake St. Clair, I remember her being surprised when I mentioned that I’d liked her piece. On the Austlit database, I notice that both these works were in the same issue, number 70, published in Autumn 1997. For me, this must have been a tipping point of sorts.

I remember that in the previous year, or perhaps the one before it, I’d chosen to do a study on Richard Flanagan for a high school English class. There wasn’t a lot to study at that time. Death of a River Guide had been published, and Richard was kind enough to do a short phone interview where I offered unwieldy questions and hopelessly tried to record his responses with a rubbish tape recorder placed against the old-fashioned dial-up phone downstairs.

I remember the invitation to the launch of Death of a River Guide sitting on my mother’s fridge in 1994.

There has been a lot of talk about how Richard Flanagan’s Man Booker prize win will raise the profile of Tasmanian writing internationally. Senator Christine Milne, quoted in The Sydney Morning Herald, stated that “Richard…has now put us firmly on the global literary map.[1]”

It’s been an oft-repeated sentiment, as though there actually was a global literary map.

And it might be a little bit true. But I believe it is looking at the matter in a wrong-headed, brand-centric way. Certainly, the win puts Flanagan’s writing on the world stage – deservedly – but most readers are content with a representative exotic from any particular region. They follow writers, not regions. Perhaps you’ve read and loved Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Are there other Columbian novelists you’ve hunted down as a consequence of reading him?

As Tasmanians, we can be so obsessed with how others see us that we don’t take the time to reflect on how something like this might influence the way we see ourselves – one of the many reasons we might require a greater appreciation of our writers.

Perhaps the true significance of Flanagan’s win is how it can continue to make literature a reality, a live issue and a real option for young Tasmanian writers – just as it did for me twenty years ago – as well as the spectrum of Tasmanian readers. It puts literature on the front page.

Responding to 936 ABC Hobart’s question on Facebook in the wake of the win, “Who is your favourite Tasmanian author?”, one poster responded “I didnt realise we had more than one author” [sic]. Not everyone has issues of Island Magazine sitting around the house – almost nobody does. The Tasmanian literary community is fragmented and barely functional, connecting with a tiny fraction of the population.

But there will be a lot of copies of The Narrow Road to the Deep North resting on proud shelves. And it is much more important to celebrate what these novels will do for the ideas and aspirations of our developing writers, our thinkers, our historians and journalists and our scientists, than what a champagne flute on the other side of the world thinks of our distant and remote island.

[1] http://www.smh.com.au/entertainment/books/booker-winner-richard-flanagan-flogs-opinions-as-well-as-books-20141016-117awb.html

You can read, Fall on Us, by Ben Walter in the upcoming publication from Transportation Press, Islands and Cities. For updates on the release subscribe to our newsletter.

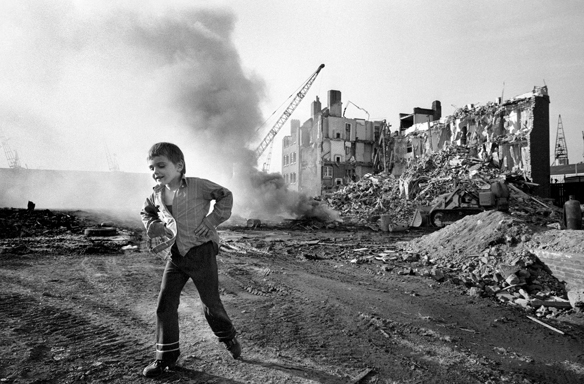

The City Once An Island That Went To The Dogs – Part II

London editor, Sean Preston looks at the island that isn’t an island, at odds with itself and the relentless change of the city it sits within.

London editor, Sean Preston looks at the island that isn’t an island, at odds with itself and the relentless change of the city it sits within.

You can go to The Isle of Dogs now, and you’ll still find ‘indigenous’ Islanders there. They’re fewer and farther between, but they’re there. But it doesn’t overturn the change of pace and face to the Island. House prices are of course indicative of its popularity. I see the same in Limehouse. The Occupyists and ‘Shire artistes squat in derelict shops and the onset is forged: The rivers will run red with their watercolours. In time, my road will fall much in the way of the rest of East London. Those that have moved here, often seeking to oppose the banking establishment, are those that trendify an area. And they have a right to, I believe. There’s no point in begrudging London’s nature, for London has always been tidal. Is this tide synthetic? Probably. I’ll not be quashed by many for suggesting that, generally, in this city, like all others, wealth will have its way.

President Ted Johns of the Republic of the Isle of Dogs didn’t stand for it for long and I believe his method of ridicule and farce as a political tool made much sense. I have argued, perhaps to my detriment in some corners, that trolling is the great art of our time. I really do believe that to be the case (and look at it this way, if it proves not to be, I can always pretend I was just trolling). From his presidential home, which was in fact a small council flat on the Island, Johns and family presided over the new republic and, significantly, invited the world’s media into their home, their lives, their nation. The passports, barricades, immigration documentation, to me, are important artifacts of post-war London. And the newspaper cuttings even more so. It is known to us by now that to live by the media is to die by the media, and so it was with the independent state. The fortnight of coverage brought with it exposure of the squalor that even The Times called “Victorian”, but caused enough of a stir upstairs that the full tabloided onslaught was visited upon it.

Humour, bizarrely, has to be at the centre of our endeavours against those that seek to garrote social equality. Irony as a defense mechanism is nothing new; it’s unreservedly London, English. Literature has a part to play in this, and has been the primary canvas of insurrection and mockery for as long as we’ve scribbled. It’s hard to know how relevant, or how conspicuous this form of literary fiction can be in the century already well underway. I suppose the one thing about the oppression of opinion labelled extreme by those that gain from doing so, is that it requires the artist – the writer – to augment their creativity, just as Ted Johns did, abruptly, sensationally, for a fortnight in 1970.

The City Once An Island That Went To The Dogs – Part I

London editor, Sean Preston looks at the island that isn’t an island, at odds with itself and the relentless change of the city it sits within.

Londoners will know to which area the riddled title of this piece refers, the rest of the world, perhaps not. The Isle of Dogs isn’t an island, not really. It’s a peninsula in London and an area unlike no other, enriched with the fog of a confused identity. Once the home of mass and abject poverty, often degradation, community, Dockers, now the home of mild gentrification, marginalized poverty, and of course, what we call “The City” which is in fact London’s vainglorious project of the last part of the 20th Century in the form of skyscrapers that line the north of the Island, blocking out the sun. It’s East London, but sort of sits in the South and feels like it too, drooping, weighing down our Thames and bending it all out of shape. The Isle of Dogs has been threatening to burst for centuries. I wonder if all of London would seep down through it, down the plug, into the Garden of England via Bromley.

Abruptly, sensationally, for a fortnight in 1970, it became an independent state. In a move unavoidably likened to the Ealing comedy Passport To Pimlico, Labour’s Ted Johns, originally from Limehouse where I live, and a man of some lineage (his forebearers were involved in the Dockers’ Strike of 1889 and fought against Franco’s brand of Fascism in the Spanish Civil War), issued a Unilateral Declaration of Independence as a reaction to, primarily, poor facilities for its some 10,000 residents of the topographic wonderland. The Island had been pushed as far as it could withstand. Paucity was a way of life, and with it anger. Routinely, the Islanders were overlooked, ignored, condescended. Inhabitants were treated obnoxiously by the Port authority, and Poplar’s Labour, a political party they backed unreservedly, seemingly ignored them. So too did Tower Hamlets which later encompassed the Island. It was time for regime change. It was time for President Johns. Of course, the move was always going to be more a statement (a crucially well-covered light trolling of the authorities) than it was a military coup with geographical longevity.

Within this anomaly in time, we see a microcosm of what was to come in East London. Gentrification, state-led or otherwise, is paramount for all of us to see. It’s the theme storified in pubs over pints. A friend of mine, rather crudely, told a two-part tale: In 2001 he was offered full board by a lady of Dalston’s night for a nominal figure. Just ten years later, he couldn’t get a pint for the same price in the same area. I laughed recently when another friend told me that the name Poppy, a name presumably favoured for baby daughters by the money-classed new parents of the eighties, was short for Pop-Up Shop. We joke, but Working Class Inner London is on its way out. Perhaps it’s this nagging truth that draws me to East London’s local history. There’s something rather horrendous to watch, most would agree, in the act of uprooting a tree. It seems cruel and tasteless, and I say that as someone not known for his environmentalist sympathies. The Islanders knew that troubles lay ahead in this respect. Microlocalism is important to those with little else. They were going to be dug up and chucked out. Not immediately, not barbarically, and not unlike the undesirables of London are being tossed asunder now. Quietly, permanently, eradicated.

Read more on the Isle of Dogs next week.